Universal Pre-K in Tulsa: A Surprising Success

One of the nation’s oldest universal pre-K programs amasses evidence of positive outcomes into the college years.

Oklahoma’s universal pre-K (UPK) program has long been a classic “man bites dog” story. In 1998, Oklahoma became the second state in the U.S. to offer free pre-K to all four-year-olds. That successfully implemented program produced eye-popping results: impressive gains in prereading, prewriting, and premath skills.[1] Follow-up studies of Tulsa’s UPK program by my team at Georgetown University revealed encouraging evidence of persistence of benefits as students moved through elementary school, middle school, and high school. Most recently, we found that Tulsa’s UPK program is linked to a 12 percentage-point boost in college enrollment many years later.[2] We also found that the benefits of Tulsa’s UPK program outweigh the costs by nearly 3 to 1.[3]

Coupled with growing evidence of the critical importance of the early years in brain synapse formation, results like Tulsa’s have encouraged state and federal officials elsewhere to consider UPK. Strong support from the business community has also fueled the UPK movement. As of 2023, nine states and Washington, DC, have adopted a policy that might reasonably be described as UPK. Almost every other state has a targeted pre-K program. Many cities have established their own UPK programs, including Washington, DC, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, New York City, San Antonio, Seattle, Philadelphia, Portland, Oregon, and others.

As of 2023, nine states and Washington, DC, have adopted a policy that might reasonably be described as UPK.

At the federal level, Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden have advocated UPK. While the Obama administration’s program never got serious consideration from Congress, the Biden administration’s plan came within one vote of becoming law in December 2021.

Why Study Tulsa?

At Georgetown University, a multidisciplinary team has been studying Tulsa’s UPK program since 2001.[4] We did so not only because Oklahoma was one of the earliest states to adopt UPK; it also has one of the nation’s highest pre-K participation rates—70 percent. Tulsa is the state’s largest school district, and it has long featured a diverse student body: In the fall of 2006, the kindergarten class was 35 percent White, 31 percent Black, 23 percent Hispanic, and 9 percent Native American. Tulsa boasts not just one strong pre-K program but two: the Tulsa Public Schools (TPS) UPK program and the CAP of Tulsa County Head Start program, which receives funds from the federal government and the state UPK program.

In separate studies of students about to begin kindergarten and students about to begin preschool in the fall of 2001, 2003, and 2006, we found that the TPS UPK program produced big gains in school readiness for both disadvantaged and middle-class students. We added Head Start to the mix in 2006. For our 2005–06 preschool cohort, the TPS UPK program yielded a nine-month gain in prereading scores, a seven-month gain in prewriting, and a five-month gain in premath.[5] Head Start’s performance was also impressive, though the verbal gains were a bit weaker than those for TPS. We also found a link between the TPS UPK program and socioemotional learning, including stronger self-regulation skills and a reduction in timidity.[6]

The TPS UPK program produced big gains in school readiness for both disadvantaged and middle-class students.

To study longer-term effects, we focused on 4,033 TPS kindergarten entrants in the fall of 2006. Some of the students we studied had attended the TPS pre-K program, others had attended CAP Head Start, and the rest attended neither. In our early studies, focusing on school readiness, we compared pre-K alumni to incoming pre-K students, while controlling for date of birth and many other factors. This approach, known as a regression discontinuity design, has the advantage of strong controls for selection bias because all our control-group students were pre-K bound, just not there yet. In our later studies, focusing on longer-term effects, we compared pre-K alumni to highly similar nonalumni. This approach, known as propensity-score matching or weighting, is better suited for long-term studies, though its selection bias controls are not as strong.

When studying pre-K’s longer-term effects, researchers need to limit sample attrition. We did this by enlisting additional local school districts, the Oklahoma Department of Education, a leading virtual charter school enterprise, and eventually the Tulsa Community College and the National Student Clearinghouse as data partners. It is also important to integrate grade-retained students in the statistical analysis (because pre-K lowers grade retention) and to include outcome variables that encompass a range of possibilities. For example, as students age, they make more choices on their own. Thus, we paid close attention to which schools they enrolled in (traditional versus magnet) and which courses they enrolled in (regular versus honors, regular versus AP).

Key Findings

Over many years and studies, we reached the following conclusions about the Tulsa UPK program’s effects:

- Differences in standardized test scores between UPK alumni and nonalumni diminish considerably from kindergarten to grade 3, but math scores remain better for pre-K alumni.

- UPK alumni are noticeably less likely to be grade-retained than nonalumni. This is evident in grade 3 and remains true over time.

- In middle school, UPK alumni are more likely to enroll in honors courses, and their standardized math test scores are somewhat better.

- In high school, UPK alumni are more likely to enroll in AP or IB courses, are less likely to fail courses, and are less likely to be chronically absent.

- UPK alumni are more likely to graduate from high school on time and marginally more likely to graduate from high school.

Some of our most interesting findings come from our latest research on 18- and 19-year-olds:

- UPK alumni are 4.5 percentage points more likely to register to vote than nonalumni. Improved cognitive skills help to explain this result.

- UPK alumni are 12 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in college than nonalumni.

- Higher rates of two-year college enrollment are evident for UPK alumni who are White, Black, Hispanic, or Native American.

- Higher rates of four-year college enrollment are evident for UPK alumni who are Black or Hispanic.

The effects of Tulsa’s Head Start program are harder to estimate because of a smaller sample size. But there is a marginally significant positive relationship: Head Start alumni are 7.5 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in college than nonalumni.

If you look solely at benefits derived from higher high school graduation rates and higher college enrollment rates—a conservative estimate—the long-term benefits of UPK exceed the short-term costs by 2.65 to 1.

Tulsa’s Secret Sauce

Most studies of state-funded pre-K programs and Head Start have found positive short-term impacts on cognitive skills and, if assessed, socioemotional skills and executive functioning skills such as self-regulation and ability to plan tasks.[7]

But Tulsa’s short-term pre-K impacts are generally higher than those of other ECE programs. Why? First, Oklahoma’s pre-K law, enacted in 1998, required state-funded pre-K programs, for the most part, to be school-based and staffed by teachers with a college degree and an early childhood certificate. In other words, Oklahoma state legislators made a commitment to high-quality pre-K upfront and established public school providers as first among equals. Second, Tulsa’s Head Start program, run by CAP of Tulsa County and headed for many years by a visionary leader, Steven Dow, decided from the beginning to match the TPS pre-K program’s teacher education requirements and to match salaries and benefits too, thus ensuring a high-quality teacher workforce in a competitive environment. Under Dow’s leadership, CAP also located Head Start and Early Head Start programs in neighborhoods of color, where demand was growing. Dow’s successor, Karen Kiely, continues to provide strong leadership.

Oklahoma state legislators made a commitment to high-quality pre-K upfront and established public school providers as first among equals.

In the fall of 2005–06, we visited virtually every school-based pre-K program and Head Start program for four-year-olds in Tulsa County and systematically observed and recorded teacher practices and interactions with preschoolers. We found that the quality of the TPS pre-K program exceeded that of school-based programs in a sample of 11 other states and that the quality of the CAP Head Start program exceeded that of Head Start programs in the same 11 states.[8] In short, Oklahoma made a strong commitment to high-quality pre-K and TPS and CAP of Tulsa County implemented and sustained that commitment.

Boston’s UPK program, which has also demonstrated above-average gains in school readiness, illustrates the same point. Like Tulsa, Boston made a strong commitment not just to pre-K but to high-quality pre-K. In fact, more than Tulsa, they emphasized the value of carefully selected preschool curricula and teacher mentoring programs. Researchers found that the Boston UPK program’s effects on school readiness, like Tulsa’s, were dramatic.[9] In Boston, as in Tulsa, gains extended to disadvantaged and middle-class students.

The Boston UPK program’s effects on school readiness, like Tulsa’s, were dramatic.

Unlike studies of pre-K effects on school readiness, now as abundant as daisies in a summer meadow, there are fewer studies of longer-term effects because most UPK programs began at the end of the 20th century or later. Many of these studies find modest effects,[10] some find impressive effects,[11] and others find no long-term effects or even negative effects.[12] Our study of Tulsa’s program is not the first to show a connection between UPK and long-term outcomes, but it is the first to show what happens in elementary school, middle school, and high school.

My colleagues and I sought to explain Tulsa’s ability to sustain and broaden some of UPK’s positive short-term effects. Why, for example, does Tulsa’s program produce long-term benefits not demonstrated by randomized controlled trials of targeted programs in Tennessee and Head Start nationwide?

The first explanation, we believe, is that Tulsa’s UPK program, with high participation rates estimated at 70 percent, has encouraged elementary school educators to ratchet up their pedagogy so that students in kindergarten and first grade are exposed to more challenging material. If you know that two-thirds of your students have benefited from a high-quality pre-K program or a high-quality Head Start program, you can set higher expectations for all students in elementary school. Studies by Amy Claessens and Mimi Engel show that setting the bar higher benefits all students, not just middle-class students or high-achieving students.[13] A well-crafted study by Elizabeth Cascio finds that UPK programs generally produce better outcomes than targeted programs, especially for disadvantaged students.[14] In all probability, positive peer effects also help to account for the UPK advantage.

A second explanation for Tulsa pre-K’s long-term effects is the presence of strong magnet schools in TPS. Students who attended TPS pre-K are more likely to attend a magnet middle school, a magnet high school, or both.[15] This is important because, at least in Tulsa, the magnet schools are better than traditional schools. A student whose intellectual curiosity has been whetted in preschool and who builds on that foundation in elementary school is more likely to attend a magnet school. In such settings, students take advantage of opportunities to take more challenging courses. They may also benefit from positive peer effects. For Black students in particular, school suspension rates are noticeably lower in magnet schools, which reduces the likelihood that these students will be discouraged, distracted, or derailed on their educational journey.[16]

For Black students in particular, school suspension rates are noticeably lower in magnet schools.

A third factor is the presence of Tulsa Achieves. Established in 2007, this program provides free community college to all Tulsa County students who have earned a 2.0 GPA or better in high school. It is one thing to tell K-12 students that they ought to aspire to a college education and lay the groundwork for this by doing their homework, attending class, and so on. It is another thing to tell them, confidently, that an inability to afford college tuition will not pose a barrier for the first two years. A legitimate concern is that such a program might discourage students from seeking or obtaining a B.A. degree, which offers even higher economic benefits than an A.A. degree. However, a study of Tulsa Achieves shows that attending Tulsa Community College, if anything, leads to more bachelor’s degrees down the road.[17]

From Preschool to College

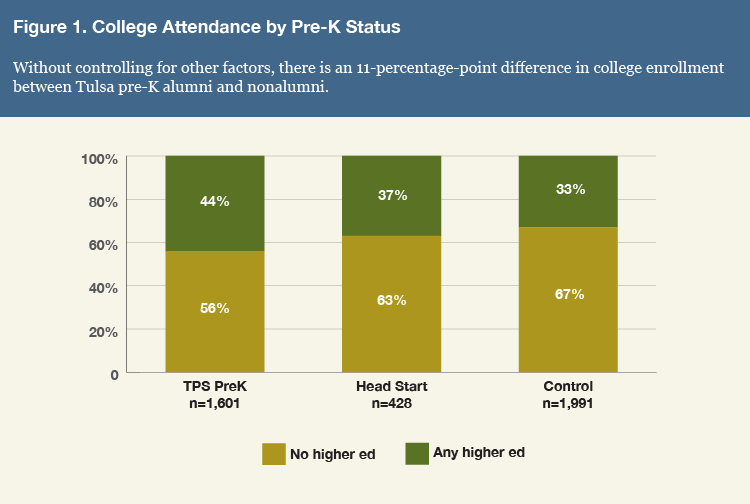

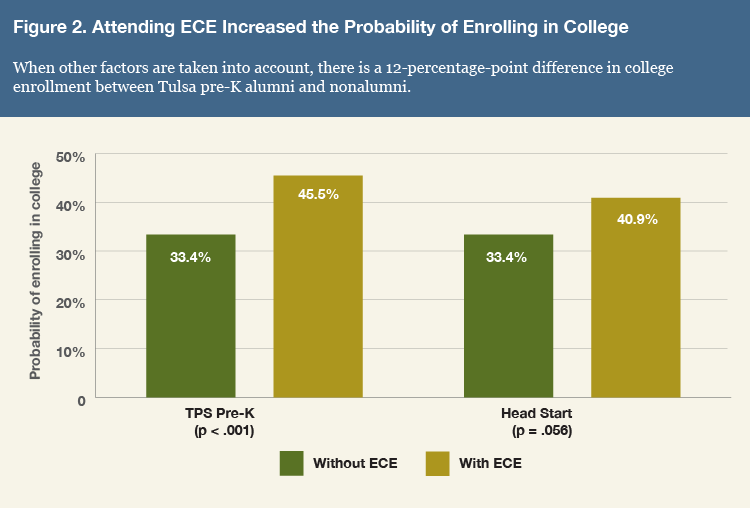

The descriptive statistics alone, without controlling for other factors, show an 11 percentage-point difference in college enrollment between Tulsa pre-K alumni and nonalumni (figure 1). When other factors are taken into account, using a technique known as propensity score weighting, there is a 12 percentage-point difference in college enrollment between Tulsa pre-K alumni and nonalumni (figure 2).

My colleagues and I have three reasons for trusting our results. First, unlike many researchers conducting longitudinal studies, we have an extraordinary array of demographic information, thanks to a parent survey conducted in August 2006: gender, race/ethnicity, date of birth, mother’s education, the presence of the biological father at home, the primary language spoken at home, internet access, and an estimate of the number of books at home, for example. This richness enabled us to identify control-group students who most closely resembled treatment-group students and to control for differences in the two where they exist. It makes for a fairer comparison.

Second, our original study used a regression discontinuity design, which one can expect to better control for selection bias than many alternative research approaches. However, when we compared findings at kindergarten entry using both regression discontinuity and propensity-score matching techniques, the effects of Tulsa’s UPK program using our original regression discontinuity design were stronger. Thus, we do not believe that our subsequent use of a propensity-score design artificially inflated the program’s impacts.

Third, while the strongest research design, a randomized controlled trial, was not an option for our study in Tulsa, it was used to study the long-term effects of Boston’s UPK program. Guthrie Gray-Lobe and his colleagues found an 8 percentage-point difference in college enrollment for UPK alumni compared with nonalumni.[18] Though not quite as high as the 12 percentage-point difference we found in Tulsa,[19] it is similar enough to support the following conclusion: UPK is associated with a significantly higher likelihood of college enrollment.

UPK is associated with a significantly higher likelihood of college enrollment.

Another way to think about Tulsa UPK is to compare program impacts with those of other early childhood interventions, as well as later interventions to boost college enrollment. Tulsa UPK looks relatively strong when compared with the Tennessee STAR experiment, for example, which investigated the effects of smaller kindergarten class sizes. It also stacks up well against programs that offer college tuition for graduating high school seniors, as exemplified by the very successful Kalamazoo Promise Program.

Conclusion

Universal pre-K has advanced significantly since it first appeared in Georgia in 1997 and in Oklahoma in 1998. Business leaders like it, parents love it, and the scientific evidence supports it.

A high-quality UPK program like Tulsa’s enhances students’ skills and their readiness to learn in the short run and sustains their motivation and academic progress all the way to college (figure 1). Students who attended Tulsa’s pre-K program are more likely to enroll in more challenging courses, more likely to pass the courses they take, and more likely to enroll in college than a comparable group of students who did not attend pre-K. The benefits of this program exceed the costs by nearly 3 to 1.

On average, universal pre-K programs are more effective than targeted programs. However, targeted pre-K programs, which serve needy children in particular, also produce considerable benefits to students, families, and society as a whole.

States that opt for universal pre-K should make sure that the benefits of universal coverage are fully realized by mixing students from different socioeconomic brackets in the same classroom. States that prefer a targeted pre-K program should locate pre-K programs in underserved neighborhoods and communities. States that see value in both approaches should actively consider hybrid strategies. For example, a state might offer full-day pre-K to less advantaged students, half-day pre-K to more advantaged students. All states should ensure that pre-K classrooms are staffed by well-educated, well-paid teachers who have credentials in early childhood education.

All states should ensure that pre-K classrooms are staffed by well-educated, well-paid teachers who have credentials in early childhood education.

As public officials consider expanding their early childhood education programs, they ought to take a closer look at Tulsa’s mature, successful UPK program. Oklahoma may not be a bellwether for all policy domains, but it is a leader in early childhood education.

William Gormley is a distinguished university professor emeritus at Georgetown University. He is also co-director of the Center for Research on Children in the United States (CROCUS). The author would like to thank Doug Hummel-Price for helpful research support. He would also like to thank the Heising-Simons Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation for their support.

Notes

[1] William T. Gormley Jr., Deborah Phillips, and Ted Gayer, “Preschool Programs Can Boost School Readiness,” Science 320 (June 27, 2008): 1723–24.

[2] William T. Gormley Jr. et al., “Universal Pre-K and College Enrollment: Is There a Link?” AERA Open 9, 1 (2023): 1–17.

[3] Timothy Bartik et al., “A Benefit-Cost Analysis of Tulsa Pre-K: Based on Effects on High School Graduation and College Attendance,” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 14 (2 (2023): 336–55.

[4] Our work is summarized on the Center for Research on Children in the United States website.

[5] Gormley, Phillips, and Gayer, “Preschool Programs Can Boost School Readiness.”

[6] William T. Gormley Jr. et al., “Socio-Emotional Effects of Early Childhood Education Programs in Tulsa,” Child Development 82, 6 (2011): 2095–109.

[7] Hiro Yoshikawa et al., “Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education” (Washington, DC: Society for Research on Child Development, 2013).

[8] Deborah Phillips, William Gormley, and Amy Lowenstein, “Inside the Pre-Kindergarten Door: Classroom Climate and Instructional Time Allocation in Tulsa’s Pre-K Programs,” Early Childhood Education Quarterly 24 (2009): 213–28.

[9] Christina Weiland and Hiro Yoshikawa, “Impacts of a Prekindergarten Program on Children’s Mathematics, Language, Literacy, Executive Function, and Emotional Skills,” Child Development 84, no. 6 (2013): 2112–30.

[10] Arya Ansari et al., “Differential Third Grade Outcomes Associated with Attending Publicly Funded Preschool Programs for Low-Income Latino Children,” Child Development 88, no. 5 (2017): 1743–56; Soliday Hong et al., “Longitudinal Study of Georgia Pre-K Program Final Report: Pre-K through 4th Grade” (Chapel Hill, NC: Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, 2023).

[11] Arthur Reynolds et al., “School-Based Early Childhood Education and Age-28 Well-Being,” Science 333 (2011): 360–64; W. Steven Barnett and Kwanghee Jung, “Effects of New Jersey’s Abbott Preschool Program on Children’s Achievement, Grade Retention, and Special Education through 10th Grade,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2021): 248–59; Kenneth Dodge, Helen Ladd, and Clara Muschkin, “Impact of North Carolina’s Early Childhood Programs and Policies on Educational Outcomes in Elementary School,” Child Development 88, no. 3 (2017): 996–1014.

[12] Michael Puma et al., “Third-Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study: Final Report” (Washington, DC: OPRE, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2012); Mark Lipsey, Dale Farran, and Kelley Durkin, “Effects of the Tennessee Prekindergarten Program on Children’s Achievement and Behavior through Third Grade,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2018): 155–76.

[13] Amy Claessens, Mimi Engel, and F. Chris Curran, “Academic Content, Student Learning, and the Persistence of Preschool Effects,” American Educational Research Journal 51, no. 2 (2014): 403–34.

[14] Elizabeth Cascio, “Does Universal Preschool Hit the Target?” Journal of Human Resources 58 (1): 1–42.

[15] Karin Kitchens, William Gormley, and Sara Amadon, “Do Better Schools Help to Prolong Early Childhood Education Effects?” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 66 (2020).

[16] Karin Kitchens and NaLette Brodnax, “Race, School Discipline, and Magnet Schools,” AERA Open 7 (2021).

[17] Elizabeth Bell, “Does Free Community College Improve Study Outcomes? Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 43, no. 2 (2021): 329–50.

[18] Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Parag Pathak, and Christopher Walters, “The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 138, no. 1 (2023): 363–411.

[19] Some of the effects of Tulsa’s UPK program on college enrollment are undoubtedly due to the Tulsa Achieves program, which may explain why Tulsa UPK’s effect on college enrollment exceeds that of Boston’s UPK program, since Boston does not offer free community college.

Also In this Issue

Opportunities and Challenges for Preschool Expansion

By Steven Barnett and Allison Friedman-KraussAs states adopt a bigger role in preschool, state leaders need to be ready to steer through tough questions of quality, access, funding, and continuous improvement.

Universal Pre-K in Tulsa: A Surprising Success

By William GormleyLongitudinal studies of Tulsa’s universal pre-K program reveal benefits to students that persist as they move through elementary and secondary school and on to college.

An Economic Perspective on Preschool for All

By David M. BlauIs “preschool for all” the best way to extend access to preschool to the children who need it most?

State Strategies for Improving Young Children’s Math Skills

By Deborah StipekEarly math instruction is as important to young learners' futures as literacy. It's time for math to get the same level of attention.

California’s Transitional Kindergarten: Lessons Learned

By Anna Powell, Wanzi Muruvi and Brandy Jones LawrenceStates can learn from California's statewide launch of transitional kindergarten, which has impacts on other ECE providers, workforce preparation and compensation, professional development, funding, and program evaluation, as well as implications for system governance.

i

i

i

i

i

i