State Strategies for Improving Young Children’s Math Skills

States can influence districts’ math curriculum choices and training of teachers and leaders, just as they have with early literacy.

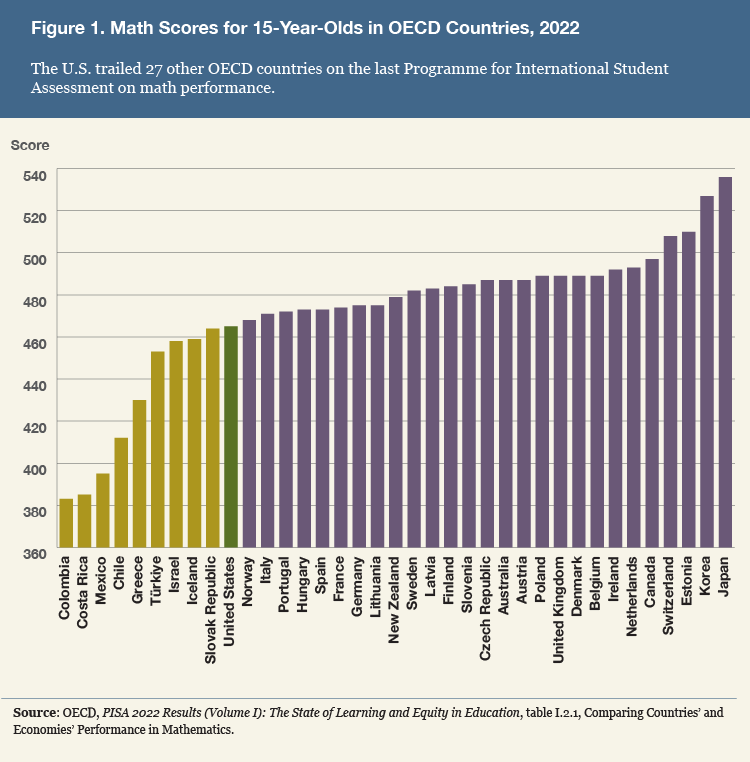

States and school districts endeavoring to improve learning outcomes for young children typically focus on literacy, not math. Math is often overlooked in improvement initiatives, and it gets far less instructional time than literacy in preschool and the early grades.[1] While literacy skills are unquestionably critical, so are math skills. This relative inattention helps explain U.S. children’s consistently poor performance in math skills relative to children in most other economically advanced countries (figure 1).

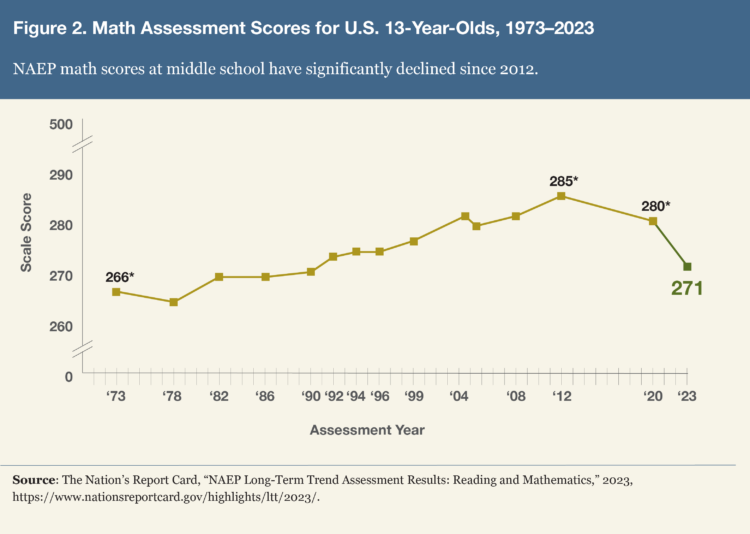

Math performance in the U.S. is declining. Math scores for 13-year-olds were dropping before the pandemic and declined precipitously during it (figure 2). Meanwhile, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. employment in math occupations was projected to grow much faster than the average for all occupations from 2022 to 2032.[2]

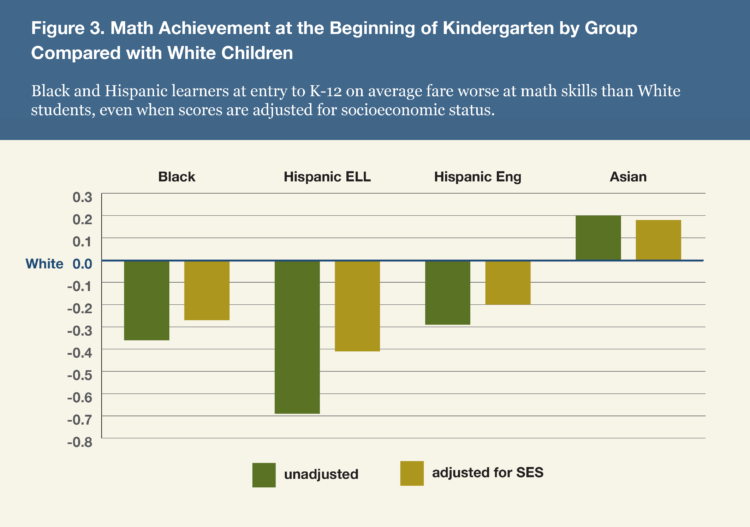

Math achievement is particularly low for children living in poverty and for children of color. The disparity starts early—before children even enter school. Figure 3 shows the math scores of a nationally representative sample of children identified as Black, Hispanic, or Asian relative to White children (represented by the “0” horizontal line). The blue bars represent the scores of different groups of children unadjusted for family socioeconomic (SES) status. The orange bars, adjusted by family SES status, show that race and ethnic differences are reduced but remain significant over and above the effect of family SES.

Studies show that children’s math skills when they enter kindergarten are highly predictive of their math achievement skills through the eighth grade.[3] Taken together, these findings make it clear that closing the achievement gap requires closing the opportunity gap and devoting attention and resources to children before school entry.

Closing the achievement gap in math requires closing the opportunity gap and devoting attention and resources to children before school entry.

One might think that the data point to preschool as the solution to closing the achievement gap. But research also clearly shows that investment in preschool alone is insufficient. Most studies of preschool show that children who participated in high-quality preschool enter kindergarten with higher math (and literacy) skills than children who did not attend. Many studies, however, also show that the preschool advantage fades over the first few years of elementary school, in part because of low-quality instruction and misalignment of the curriculum in the following grades.[4] One nationally representative study, for example, found that kindergarten teachers spent considerable time reteaching math concepts that children had mastered in preschool.[5] Thus, efforts to raise math achievement overall and to reduce the achievement gap require attention to both preschool and the early elementary grades.

Quality Matters

“P-3 alignment” has become a rallying cry of many educational reformers. But aligning bad instruction in preschool with bad instruction in early elementary is obviously not desirable. In addition to expanding attention to math in preschool and the early grades, states need to improve instruction, even as they align it across those grades.

In addition to expanding attention to math in preschool and the early grades, states need to improve instruction, even as they align it across those grades.

Early math instruction should include strands of math that are foundational to more advanced math. Math includes numbers, but in addition to counting, children need to learn concepts of more and less, ordering, grouping to make a larger unit, equal partitioning, and composing and decomposing (1+4 makes 5, as does 2+3). Math also includes patterns, which are foundational for algebra; measurement; sorting objects by such things as color, size, type, and weight; making simple charts and graphs; shapes; and spatial relations. All of these strands should be covered in preschool and the subsequent grades.

Turning to how math should be taught, effective teachers know individual children’s math skills and draw on and extend prior math knowledge, understandings, and capabilities. They focus on children’s conceptual understanding so that children develop a strong foundation for later math learning. Teachers provide planned, playful learning activities with clear learning goals. They position each student to see themselves as capable in math by giving them problems that expand their skills and by encouraging them to stick with problems they do not solve quickly.

State Levers for Increasing Math Learning

Most of the work to improve math instruction happens at the district level, but state policies affect districts’ choices. The primary levers at the state level for improving the quality of instruction, aligning instruction across the early grades, and increasing student math learning include the following: preschool program licensing and monitoring, teacher and preparation program credentialing, learning standards, assessment, curriculum, and teacher and leader capacity building.

Preschool Program Licensing Standards and Monitoring. State preschool program licensing standards and monitoring systems can be used to affect the quality of teaching in preschool. In many states, monitoring and improving are combined into what is referred to as a Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS). Programs are rated on particular dimensions, and they typically are offered support for improvement. Some states incentivize improvement by basing funding levels on a program’s QRIS rating.

State preschool program licensing standards and monitoring systems can be used to affect the quality of teaching in preschool.

Two categories of assessing quality are included in most state preschool program licensing standards and monitoring systems. The first involves “structural indices” that can be regulated relatively easily, such as teaching credentials, teacher-to-child ratios and group sizes, and elements of the physical environment considered important for safety. The second category involves “process variables” having to do with the learning environment and the quality of interactions between teachers and children and among children. Process variables are more difficult to measure and regulate.

Although not directly linked to math instruction, fewer children and lower teacher-to-child ratios support the more individualized instruction that is most effective. To assess process variables, many states include classroom observations in their QRIS system, but the observation measures currently used do not assess math instruction specifically. An observation system that provides detailed information on the quality of math instruction requires more time and training than most states consider practical to implement statewide. States could, however, support the development and use of an observation measure of math instructional quality for both preschool and the early elementary grades in districts and programs that are focused on improving early math teaching. The use of such a measure could help districts track progress in improving instruction and guide decisions about professional development (PD) for teachers. States can also require licensed programs to use curricula found in independent research to be effective.

Teacher Credentialing Requirements and Accreditation of Credentialing Programs. All states have credentialing requirements for both preschool and elementary school teachers. States vary in whether they require specific courses or provide guidelines on what credentialed teachers should know and be able to do, and some leave course requirements to the discretion of higher education programs. Math is typically given much less attention than language and literacy in state guidelines, and credentialing programs for early childhood teachers offer relatively little preparation related to the teaching of mathematics.

Credentialing programs for early childhood teachers offer relatively little preparation related to the teaching of mathematics.

Most states need to increase the emphasis on math in general and make sure they have preparation guidelines and requirements related specifically to teaching math to young children. California has made such efforts, creating a new P-3 teacher credential and offering strong guidelines on what and how teachers in these early grades should teach. State support for higher education faculty to develop their own knowledge of early math teaching and learning would also be valuable.

Student Learning Standards. Every state has learning standards for children in preschool and elementary grades, defining the math concepts that students should understand at each grade level. To promote effective teaching across the early grades, states can scrutinize the standards to make sure they include deep understanding. Some standards focus on superficial or rote skills (e.g., count to 20) and not deep understanding (e.g., that seven objects are one more than six). States can also look for misalignment between the preschool and kindergarten learning standards. If there is too much overlap, kindergarten teachers will repeat what children learned in preschool, reducing the benefits of preschool. If there is too big a gap, preschool teachers will not prepare their students to meet the demands of kindergarten.

Statewide Assessment Systems. All states have statewide assessment systems beginning in third grade. Some states have assessment systems for earlier grades, including preschool. Others leave assessment for these grades to districts’ discretion. The assessment that is used affects what is taught in schools. It signals what the state (or district) believes is important and what educators’ responsibilities are. It is thus a powerful lever for influencing what is taught, and to some degree how.

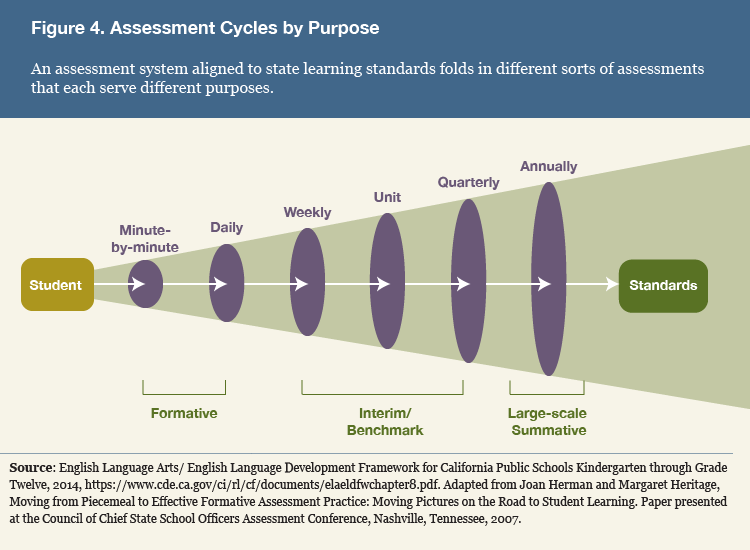

There are many kinds of assessments (figure 4). States typically focus on annual assessments aligned to the learning standards, which provide a snapshot of how well students have mastered the learning standards by a set point in time and allow state leaders to track school and districts’ progress over time. The states that implement preschool assessments do not always make the data available to elementary schools, hampering their ability to prepare for incoming students and track children’s progress across preschool and through the early elementary grades. States could help by creating a common ID for individual children and a process to make the preschool data available to elementary schools.

Annual assessments are not effective in guiding teachers’ day-to-day decisions about instruction or in helping them adjust instruction to the needs of particular students. For this, teachers need to pay close attention to students’ understandings during instruction (minute-by-minute, daily). To reduce bias (under- or overestimating student skills on the bases of irrelevant information such as race or native language) and to ensure teachers’ knowledge of all the students in their class, more systematic formative assessments should also be given periodically (e.g., weekly, unit, quarterly). These should be aligned with or ideally embedded in the curriculum so they provide information on students’ skills relevant to what they have been working on.

District and school leaders see a steady stream of commercial vendors touting particular assessments. But these decision makers rarely have strong expertise in assessment or in all subject areas, and few have the time to review the quality and fit of what is peddled. States can provide a service to districts by engaging assessment and subject-matter experts to review and provide independent evaluations of the options. Colorado, for example, recently passed legislation requiring its department of education to publish a list of evidence-informed assessment and curriculum options for math.[6]

Curriculum. States vary in the discretion they give districts in selecting the curriculum. Guidance from experts engaged by the state could help district leaders make informed choices. Recent efforts in some states to ensure that literacy curricula and practices are aligned with recent research on the teaching of reading provide a model for math.

Research on “whole child,” child-centered, play-based preschool curricula has found that they fail to produce gains in either math or literacy.[7] Only curricula that are math specific have been found to support math skill development, and there are several curricula at the preschool level that have strong research support.

Whether evaluating curricula for preschool or the elementary grades, it is useful to consider these questions:

- Is it aligned with the state’s student learning standards?

- Is it designed to develop deep understanding?

- Is it likely to promote effective teaching?

- Can students with different levels of understanding engage in the tasks and solve the problems provided?

- Does each grade build on and extend learning from the previous grade?

- Does it build in formative assessments?

Teacher Capacity Building. There is no more valuable investment a state can make than supporting teacher learning, and there is a fair amount of research about effective PD. Support for teachers is particularly important in math because many teachers of young children have doubts about their own math abilities and need opportunities to develop self-confidence as well as pedagogical skills. Research suggests that support for teachers needs to focus on clearly articulated goals and directly connect to practice.[8]

Coaching is a promising strategy and is most effective when aligned with the curriculum and the district’s vision for effective instruction so teachers do not get mixed messages. But few people have been trained to coach early math. States can help increase the number of effective math coaches for the early grades by creating a statewide coach training program. Supporting this role has the added value of offering career ladders that retain good teachers.

States can help increase the number of effective math coaches for the early grades by creating a statewide coach training program.

Most PD is planned and executed at the district or the school level, but states can encourage and support effective strategies for building teacher capacity. Lack of time is the biggest barrier to teachers’ opportunities to hone their skills. Funding models for districts that build in pupil-free days for teacher development are important. Also of value is a state-organized infrastructure for PD resources that builds in quality control. Kentucky, for example, has pending legislation that directs its department of education to help school districts identify high-quality professional development.[9] Colorado’s recent legislation requires the department of education to offer a free “train the trainer” model of teacher support in math teaching, which increases district and school capacity.

Leadership Capacity Building. States have education requirements for directors of preschools, but few require elementary school principals to receive training in early childhood education. The lack of training exists even though preschool-aged children are increasingly part of elementary schools.

States can include early childhood training in elementary principal certification requirements. States can also offer PD to school leaders in the field. Some large districts create PD for elementary school principals along with district leaders, often developed and overseen by the director of early learning. Rather than leaving this task to districts, states could more efficiently develop online programs that could serve the entire state, ideally accompanied by local on-site support. As an incentive, these learning requirements could be tied to keeping leadership credentials current.

Policies Need to Be Aligned with Each Other

A systems-based approach to implementing these strategies is key. Policies in one domain can undo policies in another. Teacher and leadership credentialing requirements, for example, need to align with student learning standards, which need to align with curricula. Teachers who are taught in their credential programs or in PD to teach math in a way that is not supported by the curriculum they use are more likely to be confused than confident and effective. Student assessment instruments that are not aligned with the student learning standards also create confusion and incoherence in teaching. To avoid such misalignments, states need to think about strategies for improving math learning as a coherent system, in which each part is supporting the other parts.

Patience is needed. The strategies described above will not yield immediate gains in math achievement. But states can monitor the implementation of these policies to assess whether the state is on track to improve young children’s opportunities to develop a strong foundation in mathematics.

Deborah Stipek is Emeritus Judy Koch Professor of Early Childhood Education at Stanford University.

Notes

[1] Deborah Stipek and Nick Johnson, “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Education Redefined: The Case of Math,” in Sharon Ryan et al., eds., Advancing Knowledge and Building Capacity for Early Childhood Research: Creating Synergies among Segregated Scholarly Communities (Washington, DC: AERA, 2020), 35–53.

[2] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Math Occupations,” Occupational Outlook Handbook, September 6, 2023.

[3] National Center for Education Statistics, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99, fall 1998, and spring 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2007; and National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics.

[4] Deborah Stipek, “Avoiding Fade Out: How to Sustain the Gains Children Make in Preschool,” Principal 99, no. 4 (2020): 42–43; Deborah Stipek et al., “PK-3: What Does It Mean for Instruction?” SRCD Social Policy Report 30, no. 2 (2017): 1–23.

[5] Mimi Engel, Amy Claessens, and Maida Finch, “Teaching Students What They Already Know? The (mis)Alignment between Mathematics Instructional Content and Student Knowledge in Kindergarten,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 35, no. 2 (2013), 157–78.

[6] Colorado House Bill 1231 (2023).

[7] Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research Consortium, Effects of Preschool Curriculum Programs on School Readiness. NCER 2008–2009 (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2008); Stipek and Johnson, “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.”

[8] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service, Toward the Identification of Features of Effective Professional Development for Early Childhood Educators: Literature Review (Washington, DC, 2010).

Also In this Issue

Opportunities and Challenges for Preschool Expansion

By Steven Barnett and Allison Friedman-KraussAs states adopt a bigger role in preschool, state leaders need to be ready to steer through tough questions of quality, access, funding, and continuous improvement.

Universal Pre-K in Tulsa: A Surprising Success

By William GormleyLongitudinal studies of Tulsa’s universal pre-K program reveal benefits to students that persist as they move through elementary and secondary school and on to college.

An Economic Perspective on Preschool for All

By David M. BlauIs “preschool for all” the best way to extend access to preschool to the children who need it most?

State Strategies for Improving Young Children’s Math Skills

By Deborah StipekEarly math instruction is as important to young learners' futures as literacy. It's time for math to get the same level of attention.

California’s Transitional Kindergarten: Lessons Learned

By Anna Powell, Wanzi Muruvi and Brandy Jones LawrenceStates can learn from California's statewide launch of transitional kindergarten, which has impacts on other ECE providers, workforce preparation and compensation, professional development, funding, and program evaluation, as well as implications for system governance.

i

i

i

i

i

i