Leveraging Community-Based Organizations for High-Dosage Tutoring

They have the knowledge and networks to expand the proven strategy for learning recovery.

In the wake of the pandemic, high-dosage tutoring emerged as the most powerful intervention to address persistent achievement gaps exacerbated by interrupted schooling. When they deliver tutoring programs with evidence of effectiveness, community-based organizations (CBOs) are uniquely poised to improve student outcomes. States and districts can take several steps to leverage this potential.

The data on student achievement in the United States continues to present a sobering reality. Recent research from Harvard University and the research and education services provider NWEA reveals an incomplete, uneven recovery.[1] There was an initial post-pandemic catch-up, funded in large part by federal relief dollars that expired in fall 2024.[2] However, progress has largely stalled, leaving many students, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, substantially behind and at risk of never catching up.[3]

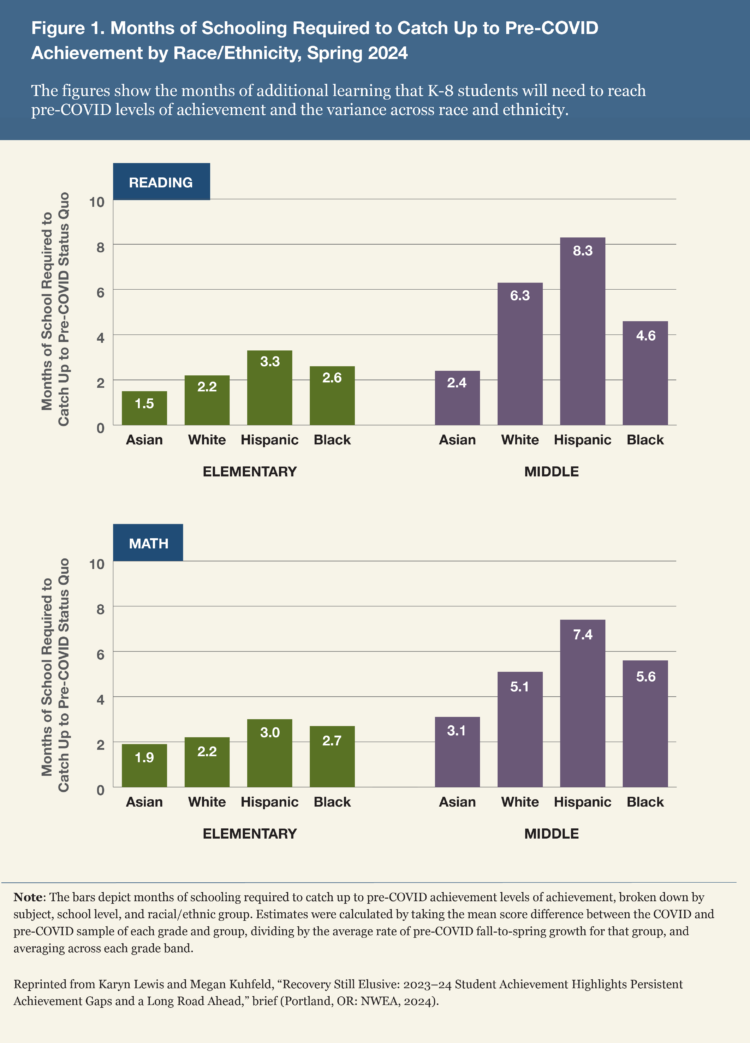

Researchers are seeking to understand the scope of pandemic-era learning loss and the widening achievement gap. A recent report by NWEA analyzed reading and mathematics test scores of 7.7 million students in grades 3 through 8 across 22,400 public schools, comparing current performance to pre-COVID baselines. Significant academic ground needs to be recovered: On average, students require nearly an additional half year of schooling to catch up in reading and math.[4]

On average, students require nearly an additional half year of schooling to catch up in reading and math.

Current middle schoolers who were in their primary years in 2020 sustained the most significant setbacks; they will require an estimated six to nine months of additional schooling to catch up to pre-pandemic levels. This means, for instance, that to prepare students to add negative fractions—a seventh grade skill—the teacher must embed a short lesson on adding fractions, which is a fourth-grade skill.[5]

Achievement disparities reveal persistent inequalities across racial and socioeconomic groups (figure 1). According to NWEA, Black and Hispanic students in elementary and middle school need the most additional months of schooling. In middle school math, Hispanic students will require 7.4 additional months, almost an extra school year, compared with 5.1 months for White students.[6] Researcher Erin Fahle and colleagues provide compelling evidence that despite several years of recovery efforts, students in economically disadvantaged communities remain significantly behind their peers in more affluent areas, deepening the preexisting academic disparities before the pandemic. Using 2023 math test scores for grade 3-8 students, researchers found that students in economically disadvantaged districts were half a year below 2019 scores compared with students in affluent communities, who were 0.2 years below 2019 scores. Gaps between the rich and poor were found at the household level, as well—while learning loss was evident across households, students from wealthier families recovered faster.[7] Learning recovery has not been an equalizer but rather an amplifier of longstanding inequities.

Clearly, there is no time to waste. Targeted, evidence-based interventions that can rapidly improve student outcomes are needed at scale. States and districts invested an estimated $7.5 billion of COVID relief funds in tutoring as a learning recovery strategy.[8] Their efforts revealed valuable lessons about what works in individualized tutoring support.[9] Successfully expanding these interventions demands policy frameworks that prioritize the use of evidence-based models, equitable access, high-fidelity implementation, adequate funding, and ongoing evaluation.

The Evidence Base

High-dosage tutoring or high-impact tutoring refers to a type of tutoring proven to be effective at closing learning gaps and improving student outcomes. This approach 1) is systematic and structured, 2) uses an empirically supported model, 3) is delivered by a consistent, trained tutor 4) is delivered on a near-daily basis, and 5) takes place during the school day for 10-36 weeks.[10] High-dosage tutoring typically targets a single subject area, ensuring consistent, concentrated support for students.

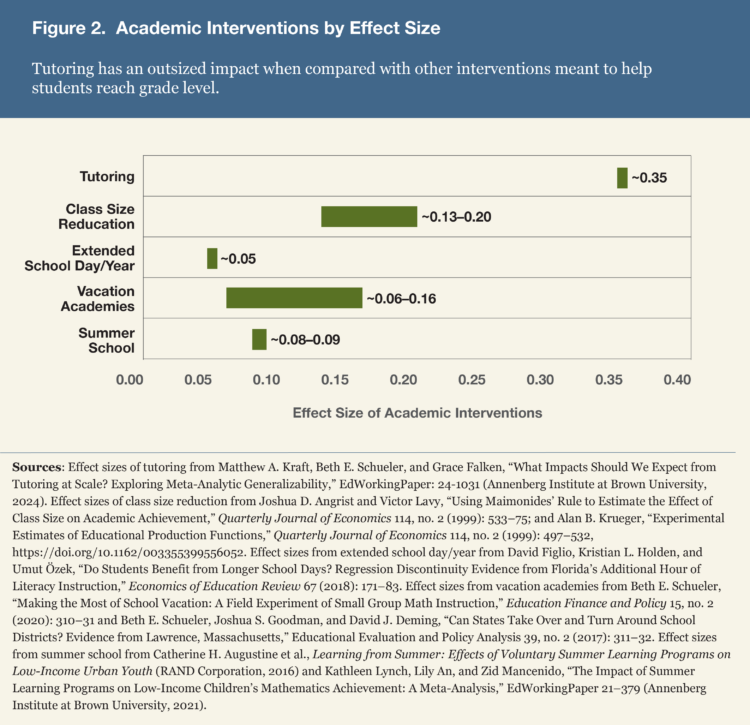

Effective high-dosage tutoring models outperform other educational interventions, such as extended school days/years, summer school, and vacation academies, in terms of student achievement gains.

Comparative analyses by researchers Matthew Kraft and Grace Falken and by Andre Nickow and colleagues show that effective high-dosage tutoring models outperform other educational interventions, such as extended school days/years, summer school, and vacation academies, in terms of student achievement gains (figure 2).[11] Using proven, integrated models during the school day can double the rate of growth in reading skills for struggling readers. Thus, students tutored for half a year can grow a full year or more in reading skills compared with counterparts not receiving tutoring.[12] Similar growth is possible in secondary math, where high-dosage tutoring can triple the amount of math high school students learn in a year, increase student grades, and reduce math and nonmath course failures.[13]

Further, highly structured tutoring models can be effective even when tutors are not certified teachers, and the human connection developed through this consistent intervention plays a vital role in student motivation and engagement.[14] These research findings have significant implications for the sustainable staffing of tutoring programs, suggesting diverse recruitment strategies that encompass local talent pools and, potentially, partnerships with CBOs.

The extensive body of research on the efficacy of high-dosage tutoring provides clear insights for policymakers, education agencies, and practitioners: Delivery of a high-dosage tutoring model by a trained human tutor during the school day holds the greatest promise of impact.[15]

High-dosage models that have been proven effective in rigorous research are structured systems that possess several interdependent components:

- structured materials or curriculum;[16]

- professional development (e.g., initial training, supervision, ongoing coaching, and feedback) for tutors aligned to the content;[17] and

- a system of assessment and data collection tools for measuring student progress and achievement.[18]

A proven tutoring model is more than a collection of best practices; it is a comprehensive system that has been implemented at scale and proven to increase student achievement.[19]

The Critical Role of Community-Based Organizations

When implemented with fidelity, high-dosage tutoring models show consistent, significant positive effects across diverse settings and student populations. With the expiration of federal relief dollars, building momentum at the local level will be critical for sustaining these supports. CBOs are emerging as potential allies in sustaining effective place-based tutoring, thanks to their ability to harness local passion, leadership, and resources.[20]

CBOs are typically local nonprofits committed to improving life for residents via needed programs and services. They possess invaluable intangible resources—extensive human-to-human networks, place-based knowledge, and a deep commitment to serving their communities. Given their relationships with families and schools through services like afterschool care, mentoring, athletic programs, and career readiness experiences, CBOs are well positioned to support educational initiatives such as high-dosage tutoring. This potential is significant, considering that there are more than 132,000 nonprofit organizations committed to youth development in the United States.

Despite testing data indicating otherwise, a majority of families do not believe their children are behind academically.[21] CBOs are uniquely equipped to bridge this perception gap, boosting family awareness and engagement with the school system and educating families about the achievement gap. They can organize local advocacy efforts around the use of effective interventions, bringing a sense of urgency at the local level.[22] As federal relief funding for public schools expires, CBOs can press states and districts to identify alternative funding streams that support a robust approach to addressing learning loss and closing gaps.

Despite testing data indicating otherwise, a majority of families do not believe their children are behind academically.

Beyond advocacy, CBOs can leverage their networks and experience to directly deliver high-dosage, school-day tutoring. For example, Literacy Mid-South, a CBO based in Memphis, Tennessee, has for over 50 years demonstrated the positive impact of community involvement in literacy initiatives serving both adults and children. In 2022, the organization expanded its literacy offerings by serving as a state-funded high-dosage tutoring partner. With funding from the Tennessee Department of Education, Literacy Mid-South launched Tutor901, a high-dosage tutoring initiative that served 4,500 elementary students during the school day between 2022 and 2024 in Memphis and Shelby Counties.[23] The work is continuing this school year with philanthropic support.

One of the most valuable assets CBOs bring is access to invested community members who can serve as tutors. The human connection in tutoring is enhanced when tutors share similar life experiences with students, increasing engagement and the effectiveness of the intervention.

While these human connections are invaluable, they are insufficient by themselves. Simply providing an adult to spend time with a student will not improve student outcomes. Many programs have offered what is essentially unstructured homework help. Studies of this approach find no improvement in learning, even if the homework help shares some of the characteristics of high-dosage tutoring.

Tutoring is a means, not an end. CBOs and their district partners must design tutoring initiatives that are grounded in evidence and address clear, specific goals. Tutoring initiatives may have goals that are directly aligned with current classroom curriculum and tier one instruction and that reinforce skills taught by teachers, or they may focus on addressing gaps in foundational skills from prior years that, while not directly connected to current classroom content, are essential for students to fully access and master that content over time. Clarity around intended outcomes is key. The goals should guide selection of a proven model, as well as the extensive planning and staff buy-in required for successful implementation. Developing a consistent tutoring schedule during the day, coaching tutors, and deploying on-the-ground support to assist tutors, connect with school staff on student progress, and monitor implementation are fundamental. Robust data collection and analysis will enable CBOs and schools to make real-time adjustments, measure impact, and guide program improvements as they go.[24]

CBOs and their district partners must design tutoring initiatives that are grounded in evidence and address clear, specific goals.

While CBO partnerships hold tremendous potential for tutoring support, districts and school leaders should vet potential partners well, just as they would any student service provider. Due diligence will encompass examination of a CBO’s existing partnerships, portfolio of services, experience working with children, and outcomes from previous academic programming. Although time-intensive, this vetting is essential for ensuring the effectiveness of the tutoring program and maximizing its impact on student achievement.

Policy Recommendations

State policymakers play a crucial role in addressing the persistent achievement gap through effective interventions like high-dosage tutoring. State efforts have grown in recent years, providing learning support to a growing number of students. These initiatives were bolstered by federal relief, which states and districts used to administer support for widespread tutoring.

Despite the expiration of these federal funds, many states are working to scale and sustain high-dosage tutoring in other ways. Since 2021, an estimated 30 states and Washington, DC, have launched a range of tutoring efforts, some rooted in legislation, that encompass incentives and resources for districts.[25] Many states have dedicated teams to provide guidance and oversight for tutoring initiatives. Some provide funding mechanisms, such as grant and matching programs, to support district-level efforts. States are also actively recruiting and training tutors and supplying vetted provider lists to ensure quality across programs. To foster innovation and best practices, some states have facilitated design sprints and tutoring pilots. Recognizing the importance of data-driven decision making, states have set up systems for collecting and analyzing tutoring program data. They have developed playbooks and webinars to contextualize research on effective tutoring and guide implementation at the local level.

Since 2021, an estimated 30 states and Washington, DC, have launched a range of tutoring efforts, some rooted in legislation, that encompass incentives and resources for districts.

States and districts can reach more students, particularly those in underserved communities, by partnering with CBOs to implement sustainable, impactful tutoring that is culturally responsive and complementary to school-based efforts. The following policy recommendations are informed by current best practices, lessons learned from existing state initiatives, and the potential of CBO partnerships. They aim to build on the work already done and embrace innovative partnerships, so states can create tutoring ecosystems that not only address immediate learning recovery needs but also establish long-term structures for ongoing academic support.

1. Create a CBO framework within a statewide tutoring initiative.

- Integrate clear guidelines for CBOs delivering high-dosage tutoring programs within already established statewide tutoring efforts that allow for local flexibility while ensuring adherence to evidence-based tutoring practices.

- Establish a rigorous vetting process for CBOs interested in providing tutoring services. Set clear criteria for approval, including demonstrated experience in working with students and schools, strong community ties and cultural competence, financial stability and organizational capacity, expertise necessary to implement academic interventions, and ability to collect, analyze, and securely store student data.

- Consider designating a point of contact for CBOs within state education agencies.

- Develop a recommended list of tutoring programs based on proven models, using resources like ProvenTutoring.org, EvidenceforEssa.org, and What Works Clearinghouse.

2. Provide funding and resources to incentivize place-based strategies.

- Allocate funding for high-dosage tutoring programs implemented by approved vendors, including vetted CBOs. Funding may be sourced through a state appropriation designated for tutoring. Additional statewide initiatives may offer funding opportunities when tutoring aligns with their program goals, such as using high-impact tutoring as a strategy to boost literacy achievement.

- Provide explicit guidance to districts on how federal funding streams that flow through state agencies (for example, Title I and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) may be braided with local funds to support a tutoring initiative.

- Offer grants or matching funds to incentivize districts to partner with qualified CBOs and provide them multiyear funding that can enable them to take their programs from pilot to scale.

- Offer guidance to develop CBO capacity in selecting and implementing tutoring models within the bounds of state regulations and frameworks like Multitiered Systems of Support and Response to Intervention.

- Provide tools like playbooks and webinars that contextualize research on effective tutoring and guide implementation.[26]

3. Establish data collection and evaluation systems for high-dosage tutoring.

- Implement a statewide system for collecting and analyzing data on tutoring program effectiveness, including on programs delivered by CBOs.

- Create policies that facilitate strong evaluation partnerships between school districts and CBOs by, for instance, establishing clear guidelines for data sharing, student selection criteria, and a standardized set of implementation and outcome metrics.

- Require regular reporting from participating CBOs and districts and make data transparent to families, schools, state leadership, and CBOs.

- Use data to inform continuous improvement and demonstrate the effectiveness of high-dosage tutoring to spur continued state and local investment.

4. Ensure equitable access to and scale of high-dosage tutoring.

- To address widening achievement gaps more effectively, set ambitious goals alongside mission-driven CBOs to significantly increase the percentage of students receiving high-dosage tutoring beyond the current 10 percent.[27]

- Prioritize funding and support for CBOs serving high-need communities and historically underserved student populations.

5. Build urgency and community engagement around high-dosage tutoring.

- Engage directly with CBOs to raise awareness about the widening achievement gap and the need for proven solutions like high-dosage tutoring.

- Leverage CBOs established relationships to collaborate with families on advocacy efforts and build local momentum.

- Support CBOs in educating and mobilizing communities around the importance of high-dosage tutoring.

These policy recommendations leverage community strengths, create a supportive environment for CBO-led high-dosage tutoring programs, and produce a system focused on academic outcomes that ensures quality implementation and data-driven decision making. Embedding high-dosage tutoring in the school day for students who need it will require time and a commitment to continuous improvement at both the state and local levels to move the needle on achievement. By ensuring that high-dosage tutoring is grounded in evidence, well-funded, and consistently evaluated for effectiveness, state boards of education can be leaders in this work.

Jennifer Bronson is managing director of programs at Accelerate, and Jennifer Krajewski is director of outreach and engagement at ProvenTutoring.

Notes

[1] Erin Fahle et al., “Education Recovery Scorecard: The First Year of Pandemic Recovery: A District Level Analysis,” report (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2024); Karyn Lewis and Megan Kuhfeld, “Recovery Still Elusive: 2023–24 Student Achievement Highlights Persistent Achievement Gaps and a Long Road Ahead,” brief (Portland, OR: NWEA, 2024).

[2] FutureEd, “How Local Educators Plan to Spend Billions in Federal Covid Aid,” explainer (Georgetown University, June 7, 2022).

[3] Fahle et al., “First Year”; Lewis and Kuhfeld, “Recovery Still Elusive.”

[4] Lewis and Kuhfeld, “Recovery Still Elusive.”

[5] Kalyn Belsha, “The Pandemic Is Over. But American Schools Still Aren’t the Same,” Chalkbeat, September 20, 2023.

[6] Lewis and Kuhfeld, “Recovery Still Elusive.”

[7] Fahle, “First Year.”

[8] FutureEd, “How Local Educators Plan to Spend.”

[9] Matthew Kraft, Danielle Sanderson Edwards, and Marisa Cannata, “The Scaling Dynamics and Causal Effects of a District-Operated Tutoring Program,” Working Paper no. 24-1030 (Annenberg Institute and Brown University, August 2024); Maria Carbonari et al., “The Challenges of Implementing Academic COVID Recovery Interventions: Evidence from the Road to Recovery Project,” research report (Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard, 2022).

[10] Carly Robinson et al., “Accelerating Student Learning with High-Dosage Tutoring,” EdResearch for Recovery: Design Principles Series (Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute at Brown University, February 2021); Amanda Neitzel et al., “A Synthesis of Quantitative Research on Programs for Struggling Readers in Elementary Schools,” Reading Research Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2022): 149–79; Andre Nickow, Philip Oreopoulos, and Vincent Quan, “The Promise of Tutoring for PreK–12 Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence,” American Educational Research Journal 61, no. 1 (2024): 74–107.

[11] Matthew Kraft and Grace T. Falken, “A Blueprint for Scaling Tutoring and Mentoring across Public Schools,” Aera Open 7 (2021): 1–21; Nickow, Oreopoulos, and Quan, “The Promise of Tutoring for PreK-12 Learning.”

[12] Nancy Madden and Robert E. Slavin, “Evaluations of Technology-Assisted Small-Group Tutoring for Struggling Readers,” Reading & Writing Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2017): 327–34.

[13] Jonathan Guryan et al., “Not Too Late: Improving Academic Outcomes among Adolescents,” American Economic Review 113, no. 3 (2023): 738–65, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210434.

21 Neitzel et al., “A Synthesis,” 149; Nickow, Oreopoulos, and Quan, “The Promise of Tutoring,” 74; Marta Pellegrini et al., “Effective Programs in Elementary Mathematics: A Meta-Analysis,” Aera Open 7 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1177/;2332858420986211.

[15] Kraft and Falken, “A Blueprint for Scaling”; Kraft, Schueler, and Falken, “What Impacts”; Robinson et al., “Accelerating Student Learning.”

[16] Kraft, Schueler, and Falken, “What Impacts”; Neitzel et al., “A Synthesis,” 149; Robinson et al., “Accelerating Student Learning.”

[17] Carly D. Robinson and Susanna Loeb, “High-Impact Tutoring: State of the Research and Priorities for Future Learning,” EdWorkingPaper: 21-384 (Annenberg Institute at Brown University, 2021); Neitzel et al., “A Synthesis,” 149; Jennifer F. Samson, Sara J. Hines, and Kathrynne Li, “Effective Use of Paraprofessionals as Early Intervention Reading Tutors in Grades K-3,” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 23, no. 2 (2015): 164–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2015.1049014.

[18] Robinson and Loeb, “High-Impact Tutoring.”

[19] Neitzel et al., “A Synthesis,” 149.

[20] Robert Balfanz and Vaughn Byrnes, “Meeting a Call to Action: Increasing People-Powered Supports in School,” report (Everyone Graduates Center, Johns Hopkins University, 2024).

[21] Tom Kane and Sean Reardon, “Parents Don’t Understand How Far Behind Their Kids Are,” New York Times, May 11, 2023.

[22] The Oakland Reach, website.

33 Literacy Mid-South, website.

[24] Accelerate and Proven Tutoring, “CBO Playbook: A Guide for Implementing an Impactful Tutoring Model,” guide (2024).

[25] National Student Support Accelerator, Stanford University, “State Tutoring Efforts and Legislation Database,” N.d.

[26] Accelerate and Proven Tutoring, “CBO Playbook.”

[27] Linda Jacobson, “Survey: Nearly Half of Students Started Last Fall Below Grade Level—Usually in Math and Reading—but Tutoring Remains Elusive,” The 74, February 9, 2023.

Also In this Issue

How States Are Investing in Community Schools

By Anna MaierPlenty more for state boards to do to foster faithful implementation of a strategy that is boosting outcomes in many communities.

California Ramps Up Support for Community Schools

By Joseph Hedger and Celina PierrottetThe state bets big on a long-term strategy to marshal resources to help the neediest students and improve their schools.

How Tennessee Is Better Addressing Workforce Needs

By Robert S. EbyActive, ongoing collaboration of businesses, K-12, higher education, and other partners is key.

Eight Ways States Can Build Better Family Engagement Policies

By Reyna P. Hernandez, Jeffrey W. Snyder and Margaret CaspeState boards can model how to engage families in decision making and guide schools and districts in best practices.

Expanding Afterschool and Summer Learning to Boost Student Success

By Jodi GrantToo many young people miss out, while community programs struggle to stay afloat.

Leveraging Community-Based Organizations for High-Dosage Tutoring

By Jennifer Bronson and Jennifer KrajewskiCommunity-based organizations have the knowledge and networks to expand the proven strategy for learning recovery.

i

i

i

i

i

i