How States Are Investing in Community Schools

Plenty more for state boards to do to foster faithful implementation of a strategy that is boosting outcomes in many communities.

At Peñasco High School in rural Northern New Mexico, a gleaming culinary arts classroom sports new stainless-steel countertops and appliances. Outside, students bake bread, cookies, and slow-roasted sweet corn kernels, or chicos, in an outdoor earth oven—a classic horno—in the culinary tradition of Ancestral Puebloan culture. Nearby, woodshop students build chairs and side tables with Spanish colonial design elements. The teacher, a graduate of Peñasco High and longtime college instructor, is a well-known local furniture maker and folk artist.

Serving about 270 K-12 students, Peñasco Independent School District became a community school district in 2021–22, with support from a state-funded grant program and other education and philanthropic sources. Peñasco employs a community school coordinator, offers project-based learning and robust afterschool programming, hosts community events like a winter light parade, and supports student wellness through a school-based health center, behavioral health partnerships, and a new wellness room at the high school.

These efforts are paying off. Since 2021–22, family and community member attendance at school events has dramatically increased, chronic absenteeism decreased from 45 percent in 2021–22 to 32 percent in 2022–23, and the high school graduation rate increased and exceeded 90 percent in 2022–23, compared with 76 percent statewide.[1]

What Is a Community School?

Arising from a research-based, comprehensive school transformation strategy, community schools organize in- and out-of-school resources and supports such as mental health services, meals, health care, tutoring, internships, and other learning and career opportunities to fit specific community needs. Through this strategy, students, families, educators, and community partners come together to support student success, often facilitated by a full-time community school coordinator. While the programs and services vary according to local context, key site-level practices include 1) expanded, enriched learning opportunities; 2) rigorous, community-connected classroom instruction; 3) a culture of belonging, safety, and care; 4) integrated systems of support to organize the delivery of wraparound services in conjunction with community partners; 5) powerful student and family engagement; and 6) collaborative leadership and shared power and voice.[2] These practices are grounded in research on community schools, as well as the science of learning and development.[3] In order to implement the practices effectively, enabling conditions—such as trusting relationships, inclusive decision making, a shared vision, and actionable data—as well as a supportive infrastructure—such as professional learning opportunities and data systems—must also be in place.[4]

Community schools can improve attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates and reduce racial and economic achievement gaps.[5] A 2017 research review identified four pillars commonly found in community schools: 1) integrated student supports, 2) expanded learning time and opportunities, 3) family and community engagement, and 4) collaborative leadership and practice.[6] These pillars have been incorporated into the federal Full-Service Community Schools grant program, as well as major local initiatives including New York City. A study of New York City’s initiative—which now has over 400 community schools—demonstrated that this strategy can work at scale.[7] Promising results include a drop in chronic absenteeism, with the biggest effects on the most vulnerable students, improved math and English language arts test scores, and a decline in disciplinary incidents.[8] Some state-funded community schools in California are also showing reductions in chronic absenteeism.[9] Finally, cost-benefit research suggests that community schools have a positive return on investment, with estimates ranging from $3 to $15 in savings for every dollar invested.[10]

While all school communities can benefit from this approach to education, some communities have more resources and can more easily establish school-community partnerships and provide support for students and families. Therefore, state investments in community schools typically target the highest-need schools and communities to direct resources in an equitable manner. This prioritization aligns with research showing that students living in low-income communities and attending underresourced schools often experience barriers to learning that community schools can help to address.[11]

Growing Support for Community Schools

Across the United States, support for community schools has grown in recent years, particularly as a strategy to address long-standing social inequities exacerbated by the pandemic. Federal funding for the Full-Service Community Schools grant program has grown fivefold, from $25 million in fiscal year 2020 to $150 million in fiscal year 2024. States, local education agencies, and community-based organizations are among the current 91 federal community-school grantees. Nationally representative survey data suggest that 45-60 percent of schools offer some form of wraparound services (e.g., mental or physical health care), a subset of which are directly implementing the community schools strategy.[12]

Across the United States, support for community schools has grown in recent years, particularly as a strategy to address long-standing social inequities exacerbated by the pandemic.

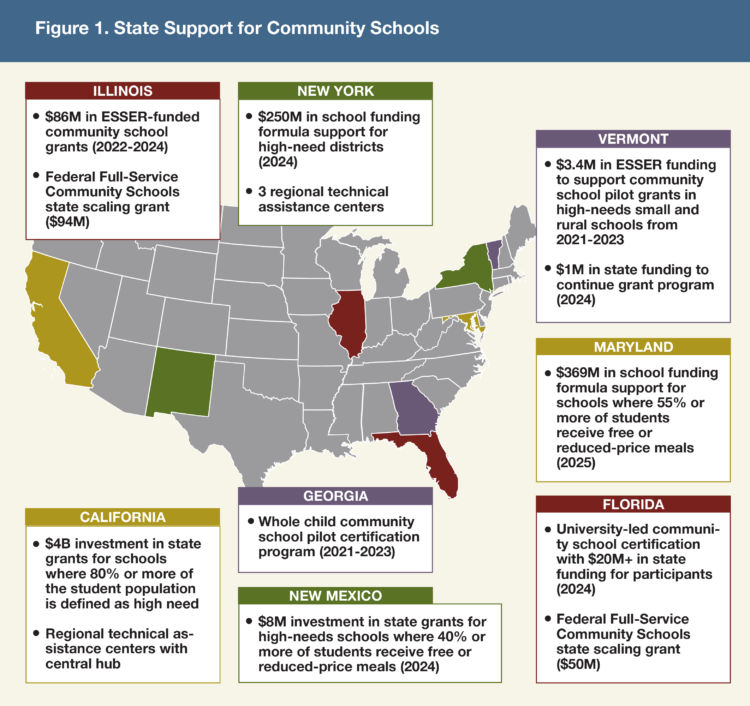

States themselves are increasingly investing in community schools. Over 30 states have community schools work underway in some form (e.g., proposed legislation, local initiatives), while at least 8 states are directly funding community schools (figure 1).[13] This movement has taken root in urban, suburban, and rural locations that represent a variety of geographic, social, and political contexts. A common thread seems to be an increasing recognition that educational outcomes are strengthened when schools support the whole child and family, including educational, social, emotional, and physical aspects of learning, development, and wellness.

Maryland and New York have made ongoing investments in community schools through school funding formula allocations.

- As part of an education funding reform effort known as the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future, the state established the Concentration of Poverty grant program, which provides a community school coordinator, a healthcare practitioner, and per-pupil funding for programmatic supports at high-poverty schools. In fiscal year 2025, schools with 55 percent or more of students living in poverty received approximately $369 million in state funding. In addition, the ENOUGH Act provides $20 million in complementary state funding for place-based initiatives to reduce child poverty at the census-tract or neighborhood level.

- New York created a set-aside of $250 million in its school funding formula to support community school staff and services in high-needs districts. The set-aside dates back to 2016, with the amount increasing over time. New York has also funded three regional technical assistance centers to support its community schools.

Another set of states, varying greatly in size and geography, have created competitive grant programs for community schools. These grants address both planning and implementation. The funding can be used to cover assessments of assets and needs, staffing, programs and services, data collection and evaluation, and professional development.

- California has made the largest investment to date, with a historic $4.1 billion in one-time state funding to create the California Community Schools Partnership Program in 2021 and provide technical assistance to community school grantees (see separate article in this issue).

- New Mexico also provided $8 million in 2024 for community school grants, supplemented by federal school improvement dollars.

- From 2021 to 2023, Illinois used $86 million in federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding to establish the Community Partnership Grant program and help address pandemic recovery. In 2023, ACT Now—a community-based network partnering with the state—received $94 million in federal Full-Service Community Schools grant funding over five years to scale community schools in both urban and rural areas of the state.

- Vermont invested in community schools as a pandemic recovery strategy for small and rural communities, using $3.4 million in ESSER funding to develop a competitive pilot grant program from 2021 to 2023. For fiscal year 2024, Vermont committed $1 million in state funding to continue the program.

A final set of states have invested in capacity-building supports to encourage high-quality implementation. Implementation matters greatly. Not surprisingly, the longest operating and most effectively implemented community schools yield the best results for students, families, and communities.[14] Providing technical assistance and other forms of capacity building can strengthen implementation by fostering continuous improvement processes in community schools.

- Florida has supported a community schools technical assistance center and certification process developed and administered by the University of Central Florida’s Center for Community Schools. The state has provided planning and implementation grants for participating sites. State funding for this effort—known as Community Partnership Schools—has grown over the past decade from $685,000 in 2014–15 to over $20 million in 2024–25. The University of Central Florida also received a federal Full-Service Community Schools grant to develop a network of universities supporting university-assisted community schools throughout the state.

- The Georgia Department of Education created a Whole Child Model School certification pilot for community schools from 2021–23, with a goal to help community schools develop and independently sustain a whole child education model. Rather than provide direct funding, the certification process offered recognition of the work, supplied technical assistance, and helped Georgia districts and schools to blend and braid funding sources, including federal pandemic relief dollars.

Opportunities for State Policymaking

As these examples show, there are many ways that state boards of education and other education leaders can help districts and schools implement a community schools strategy.

Setting objectives. State boards have an important role in helping to identify and define key features of community schools, while also supporting robust data collection efforts. Key features can include what a community school is, what it does, and how implementation and outcomes (e.g., attendance/chronic absenteeism, school climate and discipline, academic growth and achievement, graduation rates, teacher retention) will be evaluated. The Illinois State Board of Education identified program objectives for the Community Partnership Grant, including the provision of integrated student wellness supports, expanded learning time and opportunities, active parent/guardian and community engagement, and support for LGBTQ populations.[15] The California state board approved a framework to guide implementation of the California Community Schools Partnership Program.[16]

State boards have an important role in helping to identify and define key features of community schools, while also supporting robust data collection efforts.

Funding community schools. Where practicable, state boards can work with the legislature and the state education agency to establish ongoing investment through a school funding formula allocation in the form of entitlement grants or set-asides. States can also establish competitive grant programs using education or general funds, state-directed federal funds, or a mix. Because the community schools strategy is complex and takes time to fully implement, multiyear, ongoing state commitments are important. Ongoing funding is a more predictable, sustainable source of support for districts and schools than grant programs, which might be discontinued—especially considering the staffing required to implement community schools at the school and district levels. However, grant funding can be increased over time and can serve as a precursor to an ongoing funding stream. For example, New York increased its annual school funding formula set-aside from $100 million to $250 million after an initial investment in competitive grants.

State boards can work with the legislature and the state education agency to establish ongoing investment through a school funding formula allocation in the form of entitlement grants or set-asides.

It is also important to consider how funds can be equitably distributed to serve the highest-need communities. States have defined high-need schools, districts, and student populations in varying ways—some involving complex formulas—with income measures (e.g., free and reduced-price meal or Title I status) as a key component. The California State Board of Education added a priority for rural schools to the state grant program, which targets funding to the highest-need schools in the state. The federal Full-Service Community Schools grant program also prioritizes funding for rural and Title I local education agencies.

Capacity building and technical assistance. Support is especially critical for large-scale investments and investments in schools and districts that have not previously implemented the strategy. This is another area where a state board can work with the legislature and the state education agency to ensure that adequate resources are in place. States can invest directly in technical assistance centers, as California and New York have done. As the examples from Florida and Georgia demonstrate, certification is an additional way to build capacity for implementation. Another way is to focus on blending and braiding funding sources, which is key to sustainable implementation. State boards can work with governor’s offices, state education agencies, and other systems-level partners to align compatible programs and funding sources. For example, a governor-led Children’s Cabinet can convene secretaries from various child- and family-serving agencies to develop and implement coordinated state policies and programs. Many of the states investing in community schools have a Children’s Cabinet.[17]

States are increasingly supporting and investing in community schools that offer whole-child and family supports. As chronic absenteeism and student mental health concerns persist, these investments in community schools can play an important role in meeting the needs of this moment while also providing an opportunity to reimagine how schools function.

Recommended Resources

For state leaders who would like to learn more about how to help districts launch community schools, I recommend the following resources.

- Community Schools Forward framework and resources. The Brookings Institution, the Coalition for Community Schools at the Institute for Educational Leadership, the National Center for Community Schools at Children’s Aid Society, and the Learning Policy Institute collaborated with U.S. practitioners, researchers, and leaders to strengthen the community schools field. Resources include the Essentials for Community School Transformation framework and an accompanying theory of action, outcomes and indicators guide, stages of development, technical assistance needs assessment, and costing tool.[18]

- Partnership for the Future of Learning finance guide. The Partnership produced a guide that presents strategies and examples of how to blend and braid funding sources to implement community schools.[19]

- White House funding toolkit. This federal toolkit identifies federal funding sources that may be used to support community schools, aligned to the four pillars included in the federal Full-Service Community Schools grant program: 1) integrated student supports, 2) active family and community engagement, 3) expanded and enriched learning time and opportunities, and 4) collaborative leadership practices.[20]

Anna Maier is a senior policy adviser and researcher at LPI.

[1] Anna Maier, “New Mexico Community School Profile: Peñasco Independent School District,” brief (Learning Policy Institute, 2024).

[2] Learning Policy Institute, “Framework: Essentials for Community School Transformation,” Community Schools Forward project (2023).

[3] Learning Policy Institute and Turnaround for Children, “Design Principles for Schools: Putting the Science of Learning and Development into Action,” report (2021).

[4] Learning Policy Institute, “Essentials for Community School Transformation.”

[5] Anna Maier et al., “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence,” report (Learning Policy Institute, 2017).

[6] Maier et al., “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy.”

[7] William R. Johnston et al., “Illustrating the Promise of Community Schools: An Assessment of the Impact of the New York City Community Schools Initiative,” research (RAND Corporation, 2020).

[8] William R. Johnston et al., “What Is the Impact of the New York City Community Schools Initiative?” research summary (RAND Corporation, 2020); Lauren Covelli, John Engberg, Isaac M. Opper, “Leading Indicators of Long-Term Success in Community Schools: Evidence from New York City,” EdWorkingPaper 22-669 (Annenberg Institute at Brown University, 2022), https://doi.org/10.26300/59q2-ek65.

[9] Emily Germain et al., “Reducing Chronic Absenteeism: Lessons from Community Schools,” report (Learning Policy Institute, 2024), https://doi.org/10.54300/510.597.

[10] Maier et al., “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy.”

[11] Peter W. Cookson, Jr. and Linda Darling-Hammond, “Building School Communities for Students Living in Deep Poverty,” report (Learning Policy Institute, 2022), https://doi.org/10.54300/121.698.

[12] U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, School Pulse Panel, survey, October 2024.

[13] Anna Maier and Adrian Rivera-Rodriguez, “State Strategies for Investing in Community Schools,” report (Learning Policy Institute, 2023), https://doi.org/10.54300/612.402.

[14] Maier et al., “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy.”

[15] Illinois State Board of Education, “Learning Renewal: Community Partnerships Grant,” web page.

[16] California Department of Education, “California Community Schools Partnership Program: California Community Schools Framework” (English), approved by the state board January 2022 and posted September 2022.

[17] Forum for Youth Investment, “State Children’s Cabinet Network: Network Participants” web page.

[18] National Center for Community Schools, “Community Schools Forward,” website.

[19] Partnership for the Future of Learning, “Financing Community Schools: A Framework for Growth and Sustainability,” N.d.

[20] White House, “White House Toolkit: Federal Resources to Support Community Schools” (2023).

Also In this Issue

How States Are Investing in Community Schools

By Anna MaierPlenty more for state boards to do to foster faithful implementation of a strategy that is boosting outcomes in many communities.

California Ramps Up Support for Community Schools

By Joseph Hedger and Celina PierrottetThe state bets big on a long-term strategy to marshal resources to help the neediest students and improve their schools.

How Tennessee Is Better Addressing Workforce Needs

By Robert S. EbyActive, ongoing collaboration of businesses, K-12, higher education, and other partners is key.

Eight Ways States Can Build Better Family Engagement Policies

By Reyna P. Hernandez, Jeffrey W. Snyder and Margaret CaspeState boards can model how to engage families in decision making and guide schools and districts in best practices.

Expanding Afterschool and Summer Learning to Boost Student Success

By Jodi GrantToo many young people miss out, while community programs struggle to stay afloat.

Leveraging Community-Based Organizations for High-Dosage Tutoring

By Jennifer Bronson and Jennifer KrajewskiCommunity-based organizations have the knowledge and networks to expand the proven strategy for learning recovery.

i

i

i

i

i

i