California’s Transitional Kindergarten: Lessons Learned

The state’s plans to ensure universal access to pre-K risks entrenching key inequities in parts of the system.

As part of its effort to make universal prekindergarten (UPK) available to four-year-olds, California has recently expanded transitional kindergarten (TK) in its public schools. Offered by many districts to some four-year-olds since 2012–13,[1] TK will be a full pre-K grade level in all districts by the 2025–26 school year. Other states that seek to broaden access to early care and education (ECE) can learn lessons from the challenges California has faced as it addresses the impact of TK on system governance, other ECE providers, workforce preparation and compensation, professional development, funding, and program evaluation.

Path to Pre-K for All

A cohesive, equitable birth-to-age 5 system would provide affordable, widely available options to accommodate the vastly different needs of families, particularly those with low incomes. Such a system would employ a well-supported, well-compensated workforce of experienced educators, who are often women of color and immigrant women.

Funding to realize even some part of this vision for UPK remained out of reach for decades in California. Despite being the wealthiest state in the nation, California lagged in per-pupil funding for public schools. Demand for affordable, wraparound ECE outstripped supply for all age groups. Preschool for all was limited to places like San Francisco, where then Mayor Gavin Newsom joined local advocates in passing a dedicated funding stream to support access to ECE in 2004.

One of Newsom’s first tasks when he was elected governor of California in 2018 was to develop a master plan for early learning and care. Completed in 2020, the plan called for a free, universally available preschool for four-year-olds, as well as expanded state preschool for three-year-olds living in poverty (a means-tested program implemented in schools and community-based organizations). Families of TK-age children could still choose Head Start, state preschool, or even private ECE. All these options, together with TK, were to serve as pillars of UPK. However, only TK would be funded as a universal entitlement. All other forms of ECE would fall under the universal pre-K umbrella in name only.

Completed in 2020, the plan called for a free, universally available preschool for four-year-olds, as well as expanded state preschool for three-year-olds living in poverty.

By focusing so heavily on TK, the master plan fell short of building a cohesive, equitable UPK system. There was no new funding to improve pay and working conditions for the ECE workforce—an experienced cohort, primarily women of color—outside of TK.[2] Community-based programs enrolling children with child care subsidies, for instance, would not experience a boost for serving four-year-olds as part of UPK, despite being nominally included under the UPK label.

Fractured Governance

Universal prekindergarten remains the overarching vision in California, but the label poses challenges for administrators who govern only part of a divided ECE system. Similar to many states, California’s governance of the birth-to-age 5 system is split between California’s Department of Social Services (CDSS) and the Department of Education (CDE). Before 2021, however, CDE governed the majority of ECE funding streams. Changes in 2021 moved most of CDE’s birth-to-age 5 initiatives to CDSS (with the exception of state preschool). The master plan hailed the change as “an opportunity to consolidate programs to develop a simplified and more family- and child-focused system of care,” but the move constituted a deeper split rather than a consolidation. In the same year, California’s legislature tasked CDE with bringing UPK to life. CDSS also began reforming child care subsidies, with no shared governance of the cumulative effects of both efforts on the birth-to-age 5 continuum.

Universal prekindergarten remains the overarching vision in California, but the label poses challenges for administrators who govern only part of a divided ECE system.

The deepening governance divide runs counter to movements in states such as Oregon or New Mexico, which are consolidating birth-to-age 5 programs under one department. The shift also cements a longstanding inequity in California’s ECE system: CDE focuses on the “education” component of early care and education taking place primarily in schools, while CDSS governs community-based programs representing “care.” This distinction is artificial: High-quality early learning requires thoughtful, scaffolded lessons and nurturing teacher-child interactions. No matter the setting, teaching young children will always require both “care” and “education.”

The schism has undermined system coherence. CDE bears responsibility for a cross-cutting UPK vision that includes community-based preschool, but in practice, they govern only TK and state preschool. Meanwhile, CDSS has no seat at the table in UPK governance and remains focused on subsidy rate reform, which is yet to receive a dollar of new baseline funding.

Educator Compensation

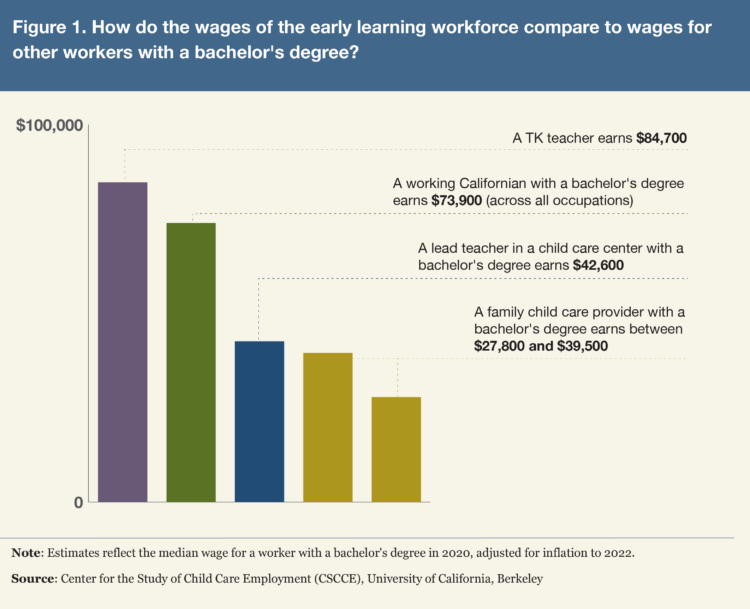

The governance divide reinforces deeply entrenched inequities in wages for the ECE workforce. A TK teacher’s annual wages are similar to the earnings of other elementary school teachers, with a median wage of $84,700 annually. Lead teachers in child care centers earn about half that; licensed home-based providers earn even less. Crucially, these figures compare wages among holders of a bachelor’s degree (figure 1).[3] The inequity disproportionately affects women of color, who comprise the majority of center-based educators and home-based providers.

Thus, early educators who transfer their expertise in child development and education to a new job in TK can double their salary. Such shifts not only promote economic justice: Current pre-K teachers are also the best-prepared candidates. Furthermore, they reflect the demographic composition of the children who enroll. As of 2020, more than two-thirds of children in TK and other preschool environments were children of color, and we estimate a similar share of center- and home-based providers were, too. Yet less than one-third of TK teachers were people of color.[4] The composition of TK teachers should shift as enrollment of four-year-olds in TK increases. But to ensure that children do not lose access to ECE, the wages and working conditions of educators in non-TK settings must also improve.

The composition of TK teachers should shift as enrollment of four-year-olds in TK increases. But the wages and working conditions of educators in non-TK settings must also improve.

California’s master plan cemented differences in workforce conditions and compensation among preschool teachers under the UPK umbrella. Yet improving compensation in ECE reduces teacher turnover and stabilizes classroom quality.[5]

Funding

As California expands to universal TK, local education agencies (LEAs) need new funding for age-appropriate facilities, equipment, and materials; staff training and a developmentally appropriate curriculum; and recruitment of new teachers and assistants. The state has already invested substantially. At full implementation, estimates peg the annual cost at $3 billion.[6] However, California has budgeted relatively few resources for the rest of the chronically underfunded birth-to-age 5 sector, even as it experiences the destabilizing impacts of TK expansion.

Over 2021–23, the state allocated $600 million in one-time funding to LEAs to get TK up and running (and to support pre-K already taking place through means-tested state preschool). There was a $500 million UPK planning and implementation grant to cover planning, hiring and recruitment, staff training and professional development, and classroom materials and supplies and a competitive $100 million early education teacher development grant, which supports TK, state preschool, and kindergarten workforce development.[7] Only $18.3 million was allocated to county ECE agencies over the same period through the UPK mixed-delivery planning grant. Moreover, the state stipulated that these funds should be used to “support relationship building” with LEAs in order to align plans for UPK expansion rather than for workforce development or support.[8]

Child care programs outside schools are struggling, evidence suggests. Analysis of the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment’s survey of child care programs in 2023 found that 46 percent of home-based family child care providers and 61 percent of centers reported fewer four-year-olds in their programs as a result of TK expansion. These providers did not necessarily flip classrooms to serve more three-year-olds. For instance, Head Start and state preschools are now dramatically underenrolled: We estimate they served an average of 55 total children per site in 2023 compared with 96 children pre-pandemic.[9]

In the absence of public support to stabilize programs against declining revenue, the loss of four-year-old enrollment to TK threatens the programs’ ability to sustain spaces for the remaining younger children, especially infants and toddlers, or to offer wraparound services outside of TK hours. California already has a severe child care shortage; it needs those spaces.

Workforce Preparation

Building a UPK workforce requires institutes of higher education (IHEs) to train and graduate educators in the competencies and skills needed to deliver developmentally appropriate curriculum for four-year-olds. Because California public schools are the main avenue for UPK, the state plans to expand the pool of credentialed teachers. Despite 10 years of partial TK implementation, California has only now turned toward addressing the educator pipeline in earnest.

Our center concluded in a 2015 study that California’s IHEs needed funding to adjust programs and produce a well-prepared TK workforce at scale, especially for teacher credential programs. In particular, we found that IHEs lacked resources to support critically needed full-time faculty positions. Furthermore, there was a mismatch between the training and preparation of educators and the requirements for TK teachers. Multiple-subject credential programs, by which elementary and middle school teachers are prepared, offered limited opportunities for prospective teachers to gain experience in TK or preschool settings. We also found that early childhood degree programs were not aligned to nor designed to meet credential program requirements.[10] Preliminary findings of a new, ongoing study suggest that little has changed.[11]

These findings highlight two critical issues. First, traditional teacher credentialing programs do not necessarily confer the ECE experience and knowledge that early childhood degree programs do. Second, California’s early childhood programs do not confer a credential; with adequate support, they could be reconfigured to do so.

California’s early childhood programs do not confer a credential; with adequate support, they could be reconfigured to do so.

Meanwhile, California is developing a new route to teaching TK via a preK–grade 3 credential. This approach could help more early educators gain credentials, but evidence from other states suggests that the overlap with California’s existing elementary/middle school credential will discourage takeup, so candidates may bypass the benefits of deep training in early education.[12]

Professional Opportunities

The success of any UPK initiative depends on a qualified, experienced workforce. During the first 10 years of TK, virtually all teachers held an elementary/middle school credential. While this pathway remains available and may continue to facilitate the transfer of some teachers from older grades to TK, prospective TK teachers will become eligible to teach through the new preK-3 credential under development. However, even the most qualified, experienced members of the ECE workforce will be required to complete a teacher preparation program before receiving a credential.

Even the most qualified, experienced members of the ECE workforce will be required to complete a teacher preparation program before receiving a credential.

To obtain the preK-3 credential, an early educator with a bachelor’s degree and at least six years’ experience will still need to complete additional coursework and clinical practice, including at least 200 hours in a K-3 setting. By comparison, K-12 teachers in private schools can apply directly for an elementary/middle school credential without additional training, even if their teaching experience covers only a single grade level. These different requirements place an undue burden on skilled preschool teachers that teachers of older grades do not face.

Inequity in the pathways to the preK-3 credential makes it harder to meet California’s demand for TK teachers, which is likely to reach upward of 15,000 by full implementation.[13] If the ECE workforce enjoyed the same flexibility offered to private school K-12 teachers, 17,000 center- and home-based educators could have qualified for a preK-3 credential in 2022, according to our center’s estimates.[14] This missed opportunity makes it much more challenging for California to meet its goals of hiring a diverse, well-prepared TK workforce.

Evaluation

The success of UPK implementation depends on the availability of credible data to help track progress and make course corrections as needed. To date, the only state-funded evaluation of TK was a two-year study of its pilot phase in 2013–14 and 2014–15.[15] That report provided a valuable first look at classroom-level indicators, but the scope did not include whether districts were prepared to mount a universal expansion. Other critical topics, like spillover effects on other parts of the ECE system, were not included.

Effectively, California missed an opportunity during the 10 years of partial TK implementation to evaluate its impact on the ECE system. Additionally, efforts to include future monitoring or evaluation have been repeatedly stricken from the state budget.[16] Moreover, the legislature did not grant CDE a preimplementation window to develop guidance on TK for LEAs, so districts have charged ahead in an approach that TK teachers in one of our recent focus groups called “flying a plane while putting it together.”

Lessons for State Leaders

States’ strategic vision should address structural factors that perpetuate inequitable wages and uneven opportunities for early educators. Building a coherent UPK system will require policy changes that remove, rather than reinforce, the structural inequities of the past. States should examine the distribution of new resources critically and move forward with policies that improve the wages and well-being of the best asset for teaching preschool: the current ECE workforce.

Split governance can undermine a coherent UPK strategy. States should adopt policies that embrace both care and education rather than building a hierarchy of programs through split governance. State agencies that are unable to govern all early education programs must still share responsibility for spillover effects in the rest of the birth-to-age 5 system.

The definition of UPK should include all ECE settings, and funding should be made available to counter the destabilizing effects of expansions to school-based prekindergarten. Community-based organizations, family child care providers, and Head Start centers can experience a sudden loss of staffing and enrollment that destabilizes their fragile businesses, robbing parents of choices.[17] States should include these programs in their UPK structure and support them in pivoting to serve younger children so overall ECE access expands.

Implementing UPK requires advance planning and the design of coherent teacher pathways that leverage existing expertise and infrastructure. States should work with the higher education community to design credentialing pathways that leverage existing expertise and infrastructure, particularly in the case of IHEs with early childhood programs. Investments are needed to help IHEs adjust their programs, including by recruitment of qualified, experienced faculty to train and supervise student teachers. IHEs also need to provide more flexible options for educators to complete degree- and preparation-related coursework and make training available in formats and spaces that are accessible to all students, including adult learners.

UPK expansion should draw on the expertise of the existing ECE workforce rather than recreating this cohort from the credentialed elementary school teacher pool. Valuing early educators’ knowledge and experience is key to meeting the demand for UPK teachers and developing a workforce that reflects the diversity of young children. States should design flexible pathways to welcome early educators into school-based classrooms. Fundamentally, credentials should not place a burden on the ECE workforce to prove their expertise in teaching four-year-olds, especially if teachers with little experience teaching young children have ready access to UPK jobs.

States must commit to programmatic data collection and reporting during implementation to ensure transparency on how the birth-to-age 5 system is shifting under UPK. Finally, implementation investments need to be paired with funds to evaluate the program, including a robust data system for ongoing monitoring of implementation efforts.

Anna Powell, MPP, and Wanzi Muruvi, PhD, are senior research and policy associates and Brandy Jones Lawrence, MPP, is a senior analyst at the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California–Berkeley.

Notes

[1] Before expansion, many districts had TK but were authorized to enroll only a subset of four-year-olds with birthdays within three months of the kindergarten cutoff.

[2] The plan did call for a process to reform subsidy rates—the state’s primary mechanism for funding ECE delivery outside of schools. However, the proposal did not call for addressing the gap between the per-child funding in these different pre-K settings. Instead, the plan focused only on strategies for improving competencies through additional education and workforce training.

[3] Anna Powell et al., “Teachers of Preschool-Age Children in California,” brief (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2023).

[5] Jessica H. Brown and Chris M. Hebst, “Minimum Wage, Worker Quality, and Consumer Well-Being: Evidence from the Child Care Market,” IZA DP No. 16257 (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2023).

[6] H. Alix Gallagher, “California’s Major Investment in Universal Transitional Kindergarten: What Districts Need to Fulfill Its Promise,” (Policy Analysis for California Education, 2023).

[7] California State Board of Education, “SBE Agenda for January 2023,” Item 10.

[8] California Department of Education, “Universal PreKindergarten Mixed Delivery Planning Grant,” web page, April 13, 2023.

[9] Refer to state-level data provided in Anna Powell et al., “The Early Care and Education Workforce and Workplace in Los Angeles County: A Longitudinal Analysis, 2020–2023,” report (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, November 2023).

[10] Lea J.E. Austin et al., “Teaching the Teachers of Our Youngest Children: The State of Early Childhood Higher Education in California, 2015,” (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2015).

[11] Leanne Elliott, American Institutes for Research Study: Assessing the Capacity of Teacher Preparation Programs, presentation, California UPK Research Design Team Meeting, January 26, 2024.

[12] R. Clarke Fowler, “Educator Licensure Overlap in the Early Grades: Why It Occurs, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It,” Kappan, July 8, 2019.

[13] Hanna Melnick, Emma García, and Melanie Leung-Gagné, “Building a Well-Qualified Transitional Kindergarten Workforce in California: Needs and Opportunities,” report (Learning Policy Institute, 2022), https://doi.org/10.54300/826.674.

[14] Anna Powell et al., “Double or Nothing? Potential TK Wages for California’s Early Educators,” data snapshot (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2022).

[15] Karen Manship et al., “The Impact of Transitional Kindergarten on California Students: Final Report from the Study of California’s Transitional Kindergarten Program” (American Institutes for Research, June 2017).

[16] A recent California Assembly bill signaled the need to evaluate the impact of TK on ECE. However, the bill had no funding attached. AB-51, Early childcare and education (2023–2024).

[17] Jessica H. Brown, “Does Public Pre-K Have Unintended Consequences on the Child Care Market for Infants and Toddlers?” Princeton University Industrial Relations Section Working Paper 626 (SSRN, December 8, 2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3360616.

Also In this Issue

Opportunities and Challenges for Preschool Expansion

By Steven Barnett and Allison Friedman-KraussAs states adopt a bigger role in preschool, state leaders need to be ready to steer through tough questions of quality, access, funding, and continuous improvement.

Universal Pre-K in Tulsa: A Surprising Success

By William GormleyLongitudinal studies of Tulsa’s universal pre-K program reveal benefits to students that persist as they move through elementary and secondary school and on to college.

An Economic Perspective on Preschool for All

By David M. BlauIs “preschool for all” the best way to extend access to preschool to the children who need it most?

State Strategies for Improving Young Children’s Math Skills

By Deborah StipekEarly math instruction is as important to young learners' futures as literacy. It's time for math to get the same level of attention.

California’s Transitional Kindergarten: Lessons Learned

By Anna Powell, Wanzi Muruvi and Brandy Jones LawrenceStates can learn from California's statewide launch of transitional kindergarten, which has impacts on other ECE providers, workforce preparation and compensation, professional development, funding, and program evaluation, as well as implications for system governance.

i

i

i

i

i

i